It’s Time to Rethink Index Funds. They Could Be More Active Than Investors Think.

Three questions index fund investors should ask.

Do you invest in index funds because you want a passive, low-cost approach to investing? If so, you may want to take a closer look at your index fund. The indices these funds track sometimes make arbitrary decisions that look more active than passive. That can leave money on the table.

For many investors, choosing a fund that simply tracks an index may sound like an easy way to get broad, passive exposure to a market or asset class. But not all indices are created equal. In a recent paper, “Indices Acting Active: Index Decisions May Be More Active than You Think,” Dimensional looked at the active decisions that go into the design and management of indices. The takeaway for investors? Think carefully about whether decisions by index providers align with your financial objectives.

Here are three questions index fund investors should ask.

1. Does any index really represent the market?

Many investors want low-cost exposure to the market and may assume that an index fund is a good way to get it. But each index provider makes its own methodology choices, which can lead to a wide range of returns among indices designed to target the same asset class. For example, the average annual spread in returns among four US total market indices over the past 20 years ranged from 0.2% to 3.2%, with an average spread of 1%1. In other words, there is no single, consistent approach to defining a market.

2. Is the index picking stocks?

Investing in a plain-vanilla index fund may sound like the opposite of stock picking. In reality, the index provider still needs to make methodology decisions that determine which securities end up being held in an index fund. Choices about which stocks to hold, at what weight to hold them, and when to rebalance are often made by arbitrary index methodology rules or sometimes by an index committee.

Even for familiar and seemingly simple market exposures, investors may be surprised by what is and isn’t in their index fund. Take, for example, the US large company market segment, commonly represented by the S&P 500 Index. Investors might guess that determining which companies count as members of the S&P 500 is straightforward, but the timing of Tesla’s inclusion in this index suggests otherwise.

In January 2020, Tesla’s stock was trading around $100 per share, making it roughly the 60th-largest company in the US by market capitalization. But Tesla hadn’t yet met all the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the S&P 500. (Among other requirements, it needed four consecutive quarters of positive earnings.) The index provider, S&P Dow Jones, later announced that Tesla would be added to the S&P 500 in December. By the day before its addition, Tesla’s stock was worth approximately $700 per share, making it the sixth-largest company in the US by market capitalization.2

Whether investors captured those gains or not depended on their choice of US large-cap index. The Russell 1000 index, for instance, included Tesla all year. The S&P 500, of course, did not. Tesla’s example is a powerful reminder that differences in index methodologies can introduce inefficiency and have substantial consequences for investor returns.

3. Are there hidden costs to investing in the fund?

People generally associate index investing with low costs. While it’s true that some index funds have very low expense ratios, there are other costs and potential performance drags that investors ought to consider.

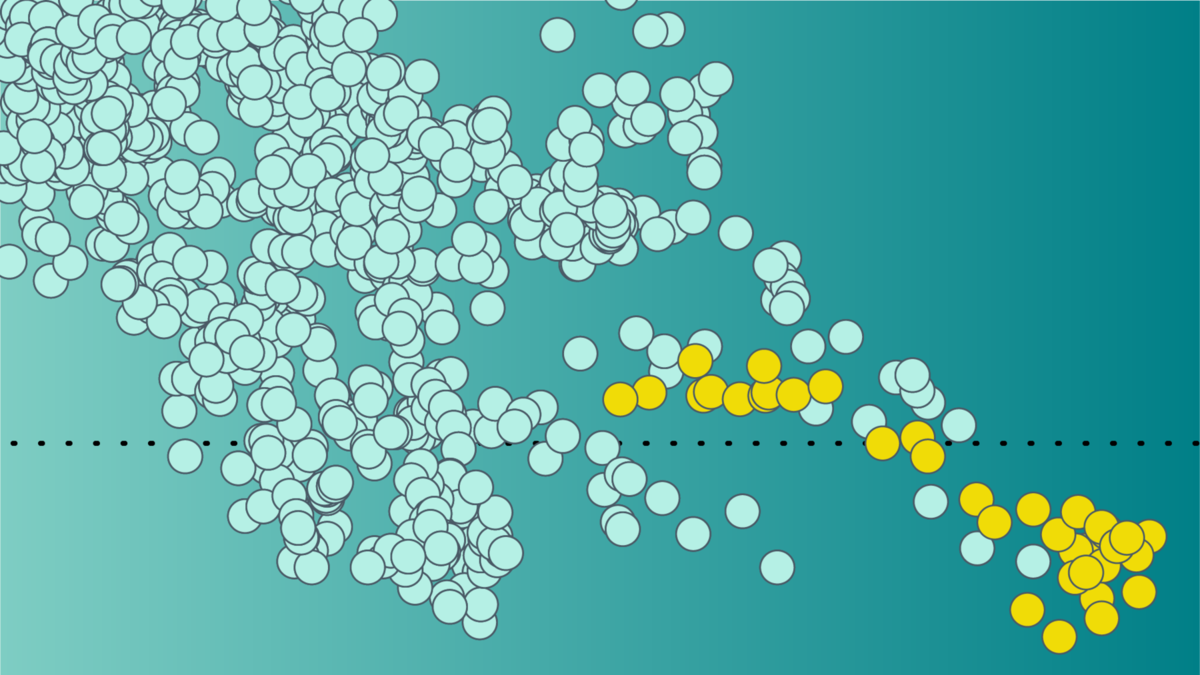

One source of hidden costs comes from many indices’ rigid approach to reconstitution. Index reconstitution events occur a handful of times each year when index-tracking funds must make trades to align positions with their indices’ holdings. Index funds seek to mimic the returns of their benchmarks. They have their hands tied during reconstitution events when it comes to how much to trade and when. An index fund manager can ensure low tracking error by trading additions and deletions at their closing prices on the reconstitution date. (Tracking error quantifies how closely a portfolio follows its index or benchmark.) This means all the assets tracking an index are likely to be trading the same stocks at the same time, potentially demanding a significant amount of trading and liquidity from the market. Other market participants are happy to provide this service to index funds, but at a cost. This reconstitution cost can be hard for investors to detect because it comes straight out of the index return.

Not surprisingly, trade volumes for index additions and deletions to major indices have tended to be unusually high on reconstitution dates. Dimensional looked at the equal-weighted average trade volume from 2018 to 2022 for the S&P 500, Russell 2000, MSCI EAFE, and MSCI EM indices, and found that on reconstitution days, trading volumes were many multiples, sometimes around 20 or 30 times, higher than typical daily trading volumes in those stocks.3 This can mean higher trading costs for the index funds trading on these days. While trading costs do not show up in expense ratios, they can reduce returns to investors.

Another area of decision-making for index providers is rebalancing. While investors may think of indexing as a “set it and forget it” way to invest, markets change every day. New companies go public, existing companies go bankrupt, and geopolitical events can introduce volatility to markets. Even if an index seeks to provide exposure to the broad market, these changes require regular adjustments. And for indices attempting to capture more targeted segments of the broad market (such as small market capitalization or value stocks), rebalancing decisions may be even more critical, as target companies move in and out of these market segments as their characteristics change.

Index providers must decide how frequently to rebalance an index to reflect market changes. While more frequent rebalancing can help limit the fund’s style drift, it can also require fund managers to execute more trades in these portfolios, adding costs that can be a drag on returns and create potential tax implications.

Do Your Homework

Index fund managers are typically judged by how closely they track their target indices, in other words, their abilities to minimize tracking error. But investors should note that tracking error is not a measure of the quality of the investment decisions made when managing a portfolio. Low tracking error does not mean investors are capturing all the returns markets have to offer. In fact, prioritizing minimizing tracking error above all other considerations can result in returns being left on the table, as managers forgo the flexibility and discretion that can drive more efficient trade execution and other return-enhancing investment decisions.

Investing involves making decisions—even in index strategies. Index providers make crucial choices about which companies’ stocks to include, when to buy and sell, and how to manage operational costs. These decisions help shape the investment exposure and returns for index investors. There isn’t a single best approach to delivering market exposure. It’s important for investors to do their due diligence on the decisions index providers make.

This piece originally appeared in Barron’s.

Footnotes

1. Indices referenced are S&P Composite 1500 Index, MSCI USA IMI Index (gross dividends), Russell 3000 Index, and CRSP US Total Market Index. S&P data © 2024 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. MSCI data © 2024, all rights reserved. Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. CRSP data provided by the Center for Research in Security Prices, University of Chicago.

2. Tesla stock price data from Bloomberg LP. Bloomberg data provided by Bloomberg.

3. Source: S&P data © 2024 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. MSCI data © MSCI 2024, all rights reserved. Bloomberg data provided by Bloomberg. Multiples of t−40 volume is the trading volume at the specific time relative to trading volume at t−40 (40 days prior to index addition or deletion). Indices change their reconstitution dates and methodologies from time to time. The data depicted during the relevant period may reflect a number of different reconstitution practices. This data does not suggest that past performance will reoccur in future periods, as index reconstitution may be different in the future. Other simultaneous events, such as triple-witching dates, could lead to spikes in volume, in addition to reconstitution dates and fund trades that follow them.

DISCLOSURES

This information is intended for educational purposes and should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell a particular security. Named securities may be held in accounts managed by Dimensional.

The information in this material is intended for the recipient’s background information and use only. It is provided in good faith and without any warranty or representation as to accuracy or completeness. Information and opinions presented in this material have been obtained or derived from sources believed by Dimensional to be reliable, and Dimensional has reasonable grounds to believe that all factual information herein is true as at the date of this material. It does not constitute investment advice, a recommendation, or an offer of any services or products for sale and is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision. Before acting on any information in this document, you should consider whether it is appropriate for your particular circumstances and, if appropriate, seek professional advice. It is the responsibility of any persons wishing to make a purchase to inform themselves of and observe all applicable laws and regulations. Unauthorized reproduction or transmission of this material is strictly prohibited. Dimensional accepts no responsibility for loss arising from the use of the information contained herein.

This material is not directed at any person in any jurisdiction where the availability of this material is prohibited or would subject Dimensional or its products or services to any registration, licensing, or other such legal requirements within the jurisdiction.

“Dimensional” refers to the Dimensional separate but affiliated entities generally, rather than to one particular entity. These entities are Dimensional Fund Advisors LP, Dimensional Fund Advisors Ltd., Dimensional Ireland Limited, DFA Australia Limited, Dimensional Fund Advisors Canada ULC, Dimensional Fund Advisors Pte. Ltd., Dimensional Japan Ltd., and Dimensional Hong Kong Limited. Dimensional Hong Kong Limited is licensed by the Securities and Futures Commission to conduct Type 1 (dealing in securities) regulated activities only and does not provide asset management services.

RISKS

Investments involve risks. The investment return and principal value of an investment may fluctuate so that an investor’s shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original value. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee strategies will be successful.